Preserving Language, Preserving Identity: Jovita González Mireles and Spanish in Texas Education

by Aída Almanza-Ferro

Bilingual education in Texas has never been a given; it has been earned, protected, and reclaimed through the dedication of teachers, families, and communities. Few individuals represent that journey more vividly than Jovita González Mireles. As a folklorist, teacher, and cultural bridge from the Texas and Mexico borderlands, Jovita González Mireles played a key role in validating Spanish as a language of scholarship and instruction in a region where it had long been marginalized (Humanities Texas, n.d.; Orozco & Acosta, n.d.; Texas State University, n.d.). Her life's work, preserved in archives and public memory, did more than introduce a new subject to the curriculum, it affirmed that the identities of Spanish-speaking students are strengths, not shortcomings. That affirmation carries powerful relevance today as colleges and universities reevaluate which programs to sustain or eliminate. The recent closure of sixteen degree programs at Our Lady of the Lake University, González Mireles’s alma mater, raises a pressing question: what do institutions choose to preserve, and what do those choices reveal about equity, culture, and belonging?

Language, Identity, and Power

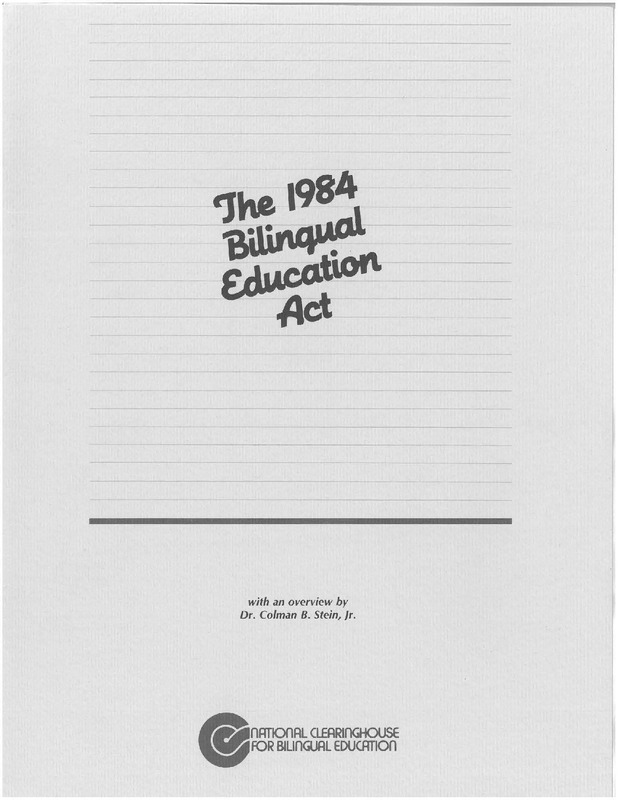

For much of the twentieth century, Spanish in Texas schools was treated as a problem to be fixed rather than a heritage to be cultivated. The policy landscape shifted unevenly, from outright suppression to gradual acceptance, which culminated in federal initiatives like the Bilingual Education Act and decades of community advocacy. Archival records show how bilingual education policy was debated and reshaped in the 1980s and 1990s, reflecting broader questions about who schools are meant to serve (University of Texas in San Antonio, 1984).

In this context, the presence of Spanish in classrooms was never just about language; they were also about power, belonging, and who counts as a legitimate subject of schooling (Bazner & Lopez, 2022). Making Spanish teachable and worthy of academic credit challenged the hierarchy that framed English as neutral and universal, while casting Spanish as local and peripheral. Jovita González Mireles’s teaching and public scholarship helped reverse that narrative by presenting Spanish as a language of knowledge, history, and artistic expression rooted in the lived experiences of border communities.

A Voice for Spanish

Jovita González Mireles (1904-1983) was born near Roma, Texas, and educated across South Texas. She studied at The University of Texas at Austin, later attended Our Lady of the Lake College in San Antonio, and built a career that wove together folklore, teaching, and public writing. Biographical accounts and archival guides trace her path from student to educator, her collaborations with figures like J. Frank Dobie, and her dedication to documenting the voices of everyday people in the borderlands. These sources portray a scholar and teacher whose authority came not only from academic credentials but also from her closeness to community memory and language (Mireles & Cotera, 2006).

Importantly, Jovita was among the first Mexican American women to formally teach Spanish in Texas. By creating space for Spanish within academic institutions, she modeled a teaching philosophy that viewed bilingualism as a strength and Spanish-speaking students as carriers of knowledge. Her approach also expanded the possibilities for who could see themselves as future educators, researchers, and cultural historians.

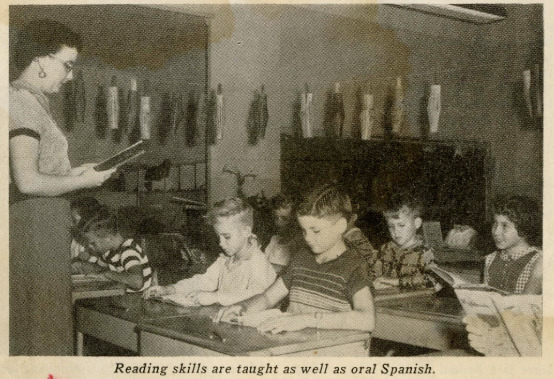

This image features adult education materials from the Mireles archival collection at the Mary and Jeff Bell Library at TAMU-CC. Visible items include a blue “Adult Basic Education” booklet with a hand-drawn figure, a bilingual tri-fold brochure titled Educación para Adultos, a flyer with blue silhouettes and the slogan “Learn Today–Earn Tomorrow,” and an older institutional pamphlet with a college seal.

The bilingual format is central. By presenting content in both Spanish and English, these materials position Spanish as a public language of learning, not just a private one. This design affirms belonging and transforms language into access, allowing adults to ask questions, enroll, and progress using the language most familiar to them. This mirrors Jovita Mireles’s advocacy for Spanish as a legitimate academic subject, not a stigmatized dialect. Her vision reframed Spanish as worthy of scholarship and professional preparation, a bridge these materials aim to build between community and formal education.

Looking ahead, this approach suggests possibilities: Spanish-medium ABE and GED programs, heritage Spanish literacy courses, credit for bilingual experience, and workforce certificates with bilingual terminology. Initiatives like family literacy nights, Spanish-first advising, and clear pathways from adult ed to college would extend Mireles’s legacy. Ultimately, the image reflects an institutional stance that values Spanish as a community asset. Preserving language in adult education isn’t nostalgic, it’s practical equity. When Spanish is visible, usable, and credit-worthy, cultural continuity and opportunity advance together.

Empowering Students Through Spanish

What does it mean for students when Spanish is recognized in school? Research on heritage language learners (HLLs) is instructive. National survey findings show that most HLLs acquire English in early childhood after first learning their heritage language; they often have stronger oral proficiency than literacy in that language and are motivated by a desire to connect with family, community, and cultural roots (Carreira & Kagan, 2011). Demographic evidence intensifies the case: between 1980 and 2019, the total U.S. population grew by 47%, while the heritage-language population grew by 194%; Spanish speakers grew by approximately 31 million and Chinese speakers by about 3 million (Center for Applied Linguistics, 2023). In other words, higher education increasingly serves multilingual students whose identities and aspirations are deeply entwined with heritage languages. These findings clarify why Spanish courses designed for HLLs, courses that cultivate advanced literacy, translation, and community-engaged learning, are not indulgences but necessities (Carreira & Kagan, 2011; Center for Applied Linguistics, 2023).

Jovita understood this long before the data was widely known. By elevating Spanish as a subject tied to lived experience, she transformed classrooms into spaces of recognition. For students from the borderlands, that recognition countered stigma and offered a path to academic success rooted in their identities.

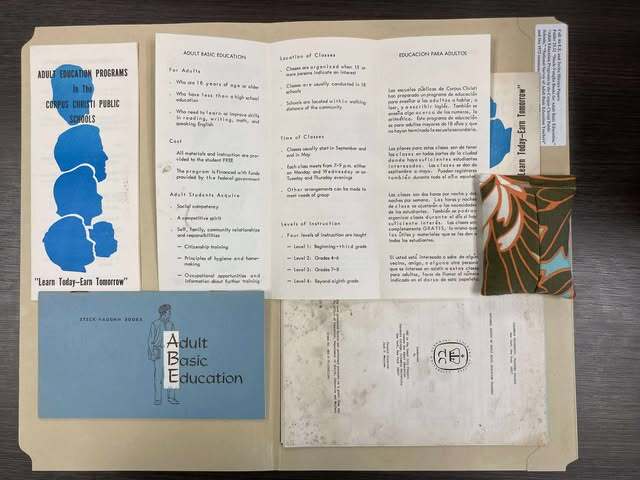

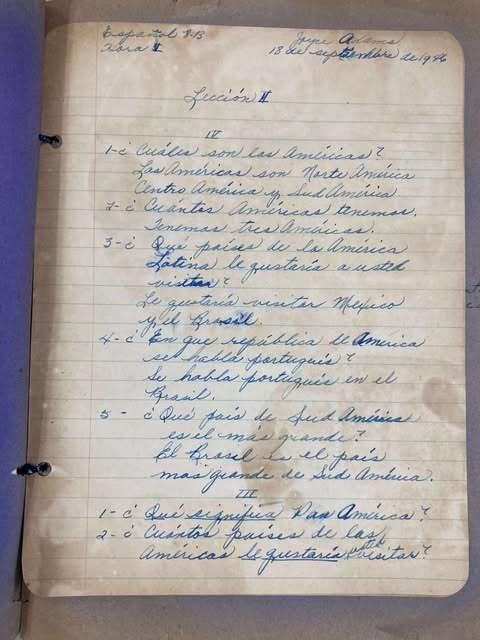

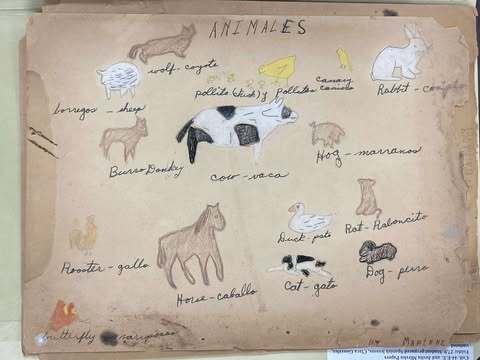

This is Jovita's Spanish class notebook, which captures everyday language learning in motion. One page features her students hand-drawn animals (a rooster, hen, and chickens) paired with their Spanish name (gallo, gallina, and pollitos). The drawings make vocabulary tactile and memorable as learners point, speak, and connect sound to image. It’s a welcoming form of visual pedagogy that invites beginner speakers to practice pronunciation, spelling, and meaning through familiar animals from daily life and family stories.

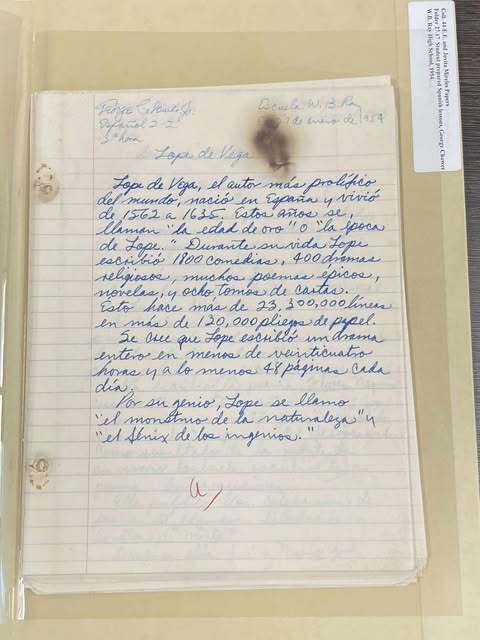

Another section of her notebook contains short essays and questionnaires written in Spanish. With this assignments, students shifted from naming to narrating, describing historical situations in Mexico with growing confidence. These essays show how vocabulary becomes sentences, and sentences become voice. They also reflect the emotional journey of bilingualism, as students explore tone, idioms, and nuance in a language often spoken at home but rarely written.

Together, these assignments trace a powerful arc, from recognition to expression. Illustrated vocabulary honors oral traditions and intergenerational knowledge, while the written pieces build academic Spanish, opening doors to school, work, and public life. This classroom practice echoes Jovita’s legacy: treating Spanish as both everyday language and a medium for scholarship.

Materials like these offer practical steps for language preservation. Visual vocabulary can be paired with family interviews, animal-themed pages can turn into student-authored storybooks, and essay prompts designed to connect home knowledge to community issues. When learners see their words on the page and their worlds in the curriculum, Spanish endures not just as a subject, but as a living bridge between identity and opportunity.

Universities and the Question of Preservation

The call to “preserve language, preserve identity” becomes especially urgent when institutions face financial pressure. In 2025, Our Lady of the Lake University announced the elimination of sixteen degree programs, affecting about ten percent of its students. Reports also noted a sharp decline in enrollment over the past decade. While university leaders described the changes as strategic and forward-looking, they raised public concern about the loss of liberal arts and culturally significant programs, including those central to Hispanic-serving missions. For a university long associated with opportunity for San Antonio’s West Side, the symbolism is powerful.

Program closures are never just administrative decisions. They affect students who lose their majors, faculty whose expertise is displaced, and communities whose histories are sidelined. When the programs at risk are those that foster bilingual and bicultural competencies, the stakes include a university’s credibility as a steward of place (Bazner & Lopez, 2022; Labaree, 2017). Jovita's legacy offers a lens for evaluation: decisions about what to preserve reflect decisions about which students, languages, and futures matter. In Hispanic-serving contexts, cutting language programs may weaken a vital pathway through which first-generation and heritage students find belonging and academic possibility.

This tension is not limited to individual institutions. In October 2025, the U.S. Department of Education eliminated funding for critical and less commonly taught languages, area studies, and global-business education, stating that these programs “don’t advance American interests or values.” The decision affected National Resource Centers, Foreign Language and Area Studies fellowships, and Centers for International Business Education and Research (CIBER), many of which serve minority-serving institutions and community colleges. These cuts disrupted multiyear research projects, halted language instruction initiatives, and undermined efforts to prepare students for careers in a globally interconnected world. Critics argue that such actions are shortsighted and risk creating an unprepared workforce, especially as global competitors continue to invest in international education (Fischer, 2025).

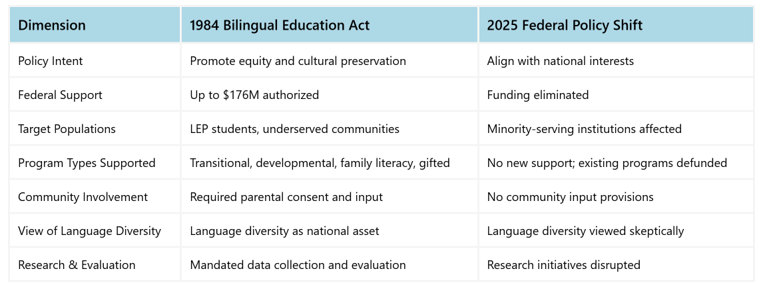

Historically, federal policy has recognized the importance of bilingual education as a matter of equity and national interest. The Bilingual Education Act of 1984 (Title II of P.L. 98-511) affirmed that children of limited English proficiency have distinct educational needs and that bilingual instruction is a primary means of learning. The Act emphasized that bilingual education benefits both English and non-English speakers, strengthens national linguistic resources, and supports cultural heritage. It authorized funding for transitional and developmental bilingual programs, teacher training, and family literacy initiatives, with a mandate to include community voices in program design. The law also required parental notification and consent, reinforcing the role of families in educational decision-making.

In light of these historical commitments, recent program cuts, whether at the federal or institutional level, signal a troubling shift. They raise questions about whether universities and policymakers still view bilingualism and cultural preservation as assets. For Hispanic-serving institutions, the erosion of language programs risks undermining their mission and marginalizing the very communities they aim to uplift.

Policy Comparison: 1984 vs. 2025

Comparing the 1984 Bilingual Education Act with the 2025 federal policy shift reveals a stark transformation in national priorities. In 1984, bilingual education was framed as a civil right and a national asset. The law recognized that language is central to identity, learning, and opportunity. It invested in programs that uplifted heritage speakers and empowered communities historically excluded from mainstream education. In contrast, the 2025 decision to defund critical language and area studies programs signals a retreat from those values.

Why Bilingual Education Still Matters

Jovita’s example invites universities to treat language programs not as expendable line items but as civic commitments. The rapid growth of heritage-language communities (Center for Applied Linguistics, 2023) and the documented profiles of HLLs (Carreira & Kagan, 2011) point to concrete academic needs: advanced literacy development for students with strong oral skills, curricular designs that connect campus learning to community life, and recognition that bilingualism is both a cultural and professional asset. Preserving and expanding Spanish and other heritage-language pathways therefore advances three interlocking aims.

First, belonging: heritage-language courses validate identities and histories, transforming campuses from sites of assimilation into spaces of dialogue and mutual recognition (Bazner & Lopez, 2022). Second, access: when programs scaffold HLL strengths toward high-level literacy, translation, and research, they convert existing competencies into new forms of academic and professional mobility (Carreira & Kagan, 2011). Third, institutional identity: for regional and Hispanic-serving institutions especially, sustained investment in language programs signals fidelity to mission and community (Labaree, 2017). Archival traces of Jovita’s teaching and scholarship remind us that today’s curricular maps rest on yesterday’s cultural labor: collecting stories, teaching across borders, and insisting that Spanish belongs in the academy (González Mireles, n.d.; Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi, n.d.; Mireles & Cotera, 2006). To preserve language is to preserve identity; to do otherwise risks forgetting the very communities that first made higher education in Texas possible.

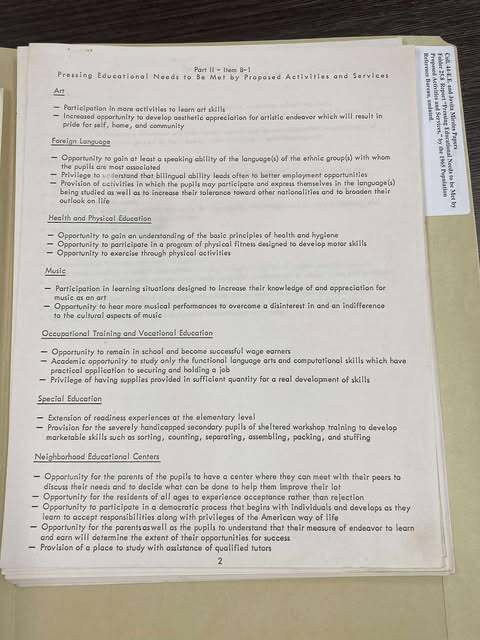

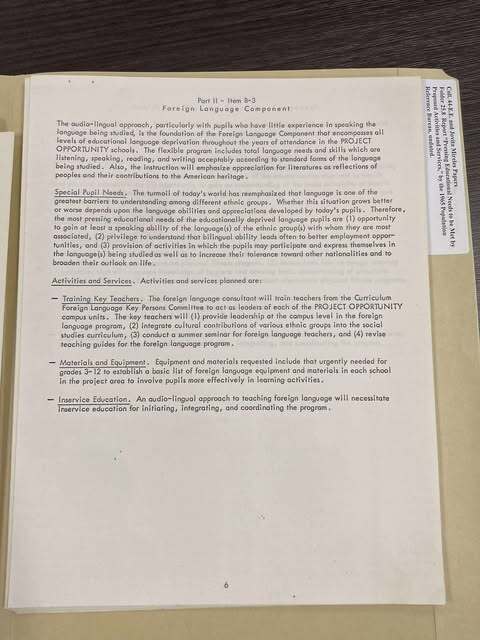

These images trace a path in Texas adult education, from personal achievement to system design, and show how language preservation is central to educational equity. First, we see the Foreign Language Proposal, with a listing of “Pressing Educational Needs” placing foreign language alongside art, health, music, and vocational training, framing bilingualism as both a job skill and a bridge to cultural understanding. Then, we have the document called “Foreign Language Component” with an audio-lingual approach, materials, teacher training, and ongoing education, which is proof that language learning was a structured goal, not an afterthought.

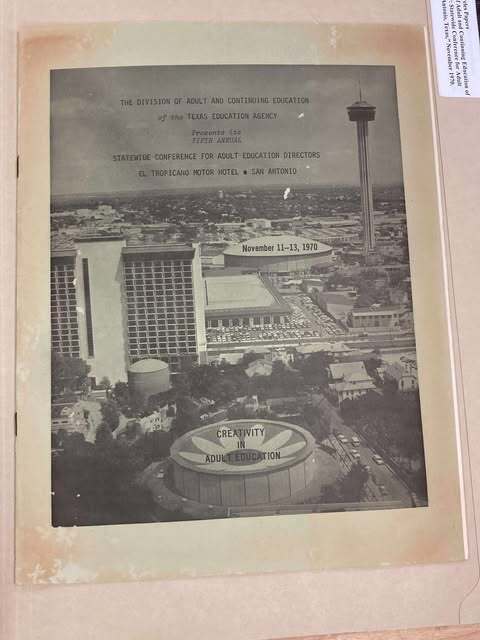

The third picture is the booklet of the Division of Adult and Continuing Education of the Texas Education Agency Conference, which was hosted in San Antonio, Texas from November 11–13, 1970. This shows that leaders were gathering to reimagine adult learning, with language policy clearly on the agenda. Lastly, we have a bigger picture of the Texas Education Agency certificate for Adult Basic Education, which marks the end of one learner’s journey. It is a formal recognition that opens doors to work, study, and civic life.

As you can see, these artifacts show how institutions tried to turn aspiration into infrastructure: training teachers, funding materials, and building systems to meet adults where they were. The foreign language pages argue for bilingualism as a public good, expanding opportunity, fostering tolerance, and honoring the languages communities already speak. This arc echoes the work of Jovita, who championed Spanish as a legitimate subject and source of intellectual authority. While the certificate celebrates a learner, Jovita fought for the conditions that make such achievements possible for Spanish-speaking communities: heritage-respecting courses, well-prepared teachers, and institutions that treat Spanish as an asset.

Reflection

Jovita González Mireles’ work to legitimize Spanish instruction in Texas schools reminds us that bilingual education is never guaranteed but the result of constant advocacy. As one of the first Mexican American women to formally teach Spanish, she transformed a language once stigmatized into a subject worthy of academic recognition, giving borderland students the confidence to see their first language as a strength. Her legacy speaks directly to contemporary debates in higher education, such as the recent program cuts at Our Lady of the Lake University, her own alma mater. The elimination of language and liberal arts programs raises critical questions about what institutions choose to preserve or discard, and what those choices reveal about their commitment to cultural identity, equity, and access. González Mireles’ example underscores the importance of safeguarding bilingual education in higher ed, not only as a curricular offering but as a form of cultural preservation and student empowerment.

References

National Association for Bilingual Education. (2025, March 3). Position statement on March 1, 2025 executive order. https://nabe.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/2025/03/NABE-PressRelease-English-Only-Executive-Order-6Mar2025-1.pdf

National Association for Bilingual Education. (2025, July 2). Urgent call to action – Immediate release of FY25 Title III ESSA funds. Texas Association for Bilingual Education. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1EA-0uAhEBBZ7zQ0Je-rNZRwZlI0T4pdf/view?usp=sharing