Women in Leadership Roles in Higher Education- Sita Gautam

Digital Exhibition

Topic: Women in Leadership Roles in Higher Education

Sita Gautam

Course: EDLD-6306 Higher Education in a Democratic Society)

Introduction: Women are significantly underrepresented in leadership positions in all sectors all around the world and the United States is no exception. Recent research has demonstrated that there is a workforce gender gap in the United States which has persisted for decades across all sectors including higher education. The problem persists both broadly and among leaders specifically. In 2021, women made up just 27.3% of the U.S. Congress, and the country has yet to elect a woman president in its history (Kalnicky, E. & Shutava, N. 2022) [1]. It can be challenging for women, especially those from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds, to advance in their careers and assume leadership positions when they adopt a concept or representation of leadership that excludes specific individuals. This can result in institutional frameworks and unconscious prejudices. Recent studies in leadership demonstrate that workplace gender gaps are not due to women leaders’ lack of ability but because of several factors such as systemic socio-cultural norms and barriers, historical gender biases, and stereotypes.

The concept of leadership has traditionally been built on specific notions of gender and race, with the belief that men and white men are the standard. Attitudes toward women leaders are less positive compared to men. It is believed that women lack the aggressiveness and competence that are stereotypically associated with strong leaders. Infact women are often perceived as communal, warm, and comforting. The second generation of gender bias, according to Ely and Kolb (2013), is pervasive and "erects powerful but subtle and often invisible barriers for women that arise from organizational structures, practices, and patterns of interaction that unintentionally benefit men while putting women at a disadvantage [2].”

Present Scenario in Higher Education in General: The American Association of University Professors reported in its 2017–2018 Annual Report on the Economic Status of the Profession that while women make up the majority of adjunct and non-tenure-track teaching positions, only 44% of these positions are tenure-track, and even fewer (36%) have led to full professorship or higher (Williams, 2021) [3]. "Women of color are especially underrepresented in college faculty and staff -- which contributes to lack of diversity, equity, and inclusion in teaching practices and curriculum as well as role models and support systems for students (Williams, 2021) [4]," according to the American Association of University Women, which lends additional weight to this finding. In addition, there are issues and discrepancies concerning compensation and promotions. The percentage of female presidents in higher education is only 32%, and their compensation is $0.91 for every $1 awarded to their male counterparts. In a similar vein, women comprise 44% of all provosts, less than half. For every $1 awarded to a male provost, female provosts receive $0.96 ( Fuesting, Bichsel & Schmidt, 2020) [5].

Present Scenario of Higher Education in Texas: In Texas, which is home to a diverse and extensive higher education system, similar trends can be observed which is evident from the “The Maroon Table Talk” discussion held on March 26, 2021, in honor of Women’s History Month by the Student Government Association’s Diversity Commission. The Panel discussion was held with Ms. Pamela Matthews, Dean of Liberal Arts College, and three other female leaders namely Ms. Deborah Thomas, Dean of the College of Geosciences; Ms. Vicki Dobiyanski, Associate Vice President in the Division of Student Affairs; and Ms Rebecca Hankins, Wendler, Endowed Professor and a Certified Archivist and Librarian at Cushing Memorial Library & Archives, clearly reflect the existence of gender biases in higher education. Such biases can undermine women’s self-worth and confidence leading to retention problems (Caitlin, 2021) [6].

Furthermore, Dr. Ginnifer Cie' Gee, Associate Vice Provost for Career-Engaged Learning of the University of Texas at San Antonio expressed the opinion that "many women face a labyrinth of barriers on their path to leadership and that the agency for each woman is different [7].” She conducted in-depth interviews with four senior-level women staff members in higher education. The barriers, which can be subtle at times, are structural (based on how society constructs gender), internal (composed of self-doubt, guilt, additional stress, and exhaustion from navigating), and cultural (created through male-oriented versions). According to Dr. Gee, leadership is not a solo journey. Supporting others is a huge part of it. Supporting and nurturing is a female characteristics. It’s also a leadership characteristic. [8].”

Efforts have been made in recent years to address such gender disparities in leadership and increase the representation of women in leadership positions within universities and colleges. There is now growing awareness of the importance of gender diversity in leadership roles and this includes targeted recruitment efforts, mentorship programs, and professional development opportunities for women aspiring to leadership roles.

Archival Resource Analysis: Texas A&M University, a public research university, was originally established as the University of Corpus Christi in the year 1947. Texas A&M University, Corpus Christi currently offers 33 undergraduate majors, 25 graduate programs, and six doctoral programs through six colleges. Its current academic staff includes female 837 (58.33%) and male 598 (41.67%). Its gender diversity at the undergraduate level includes female 3,875 (61.66%) and males 2,409 (38.34%) whereas at the graduate level, the gender diversity is females 259 (63.02%) and males 152 (36.98%). Its minority diversity includes 52% Hispanic, 35% White, 4% Black, 3% Asian, 3% two or more races, 2% International and 2% Unknown. Its Student/Faculty Ratio is 19:1 Its Full-time faculty gender distribution is male 50.1% and Female 49.9%. Part-time faculty gender distribution is female 63.5%, male 36.5% (US News& World Report) [9].

The university system is currently governed by a nine-member Board of Regents. Each member is appointed by the Governor of Texas for a six-year term and the terms overlap (all terms end on February 1 in odd-numbered years and in those years 1/3 of the regents' terms expire, though a regent can be nominated for another subsequent term). In addition, a tenth "student regent" (non-voting member) is appointed by the Governor for a one-year term.

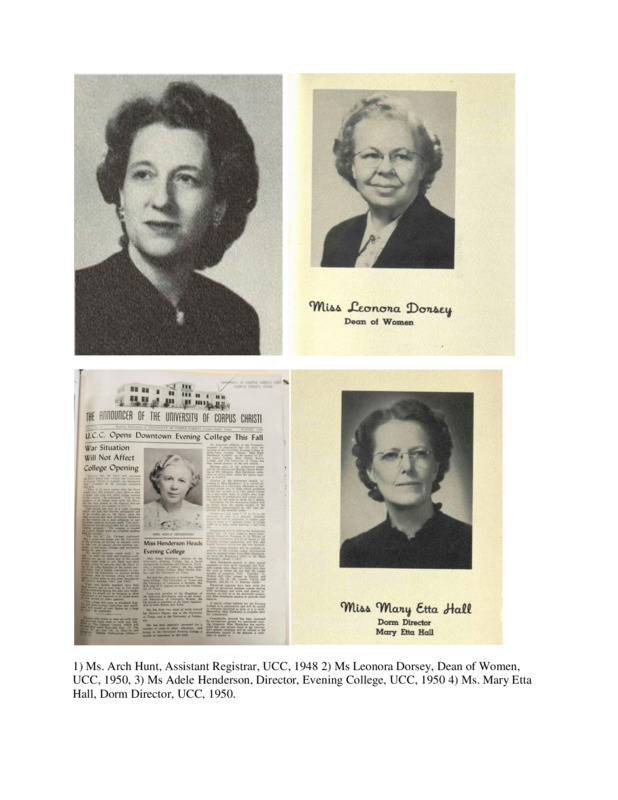

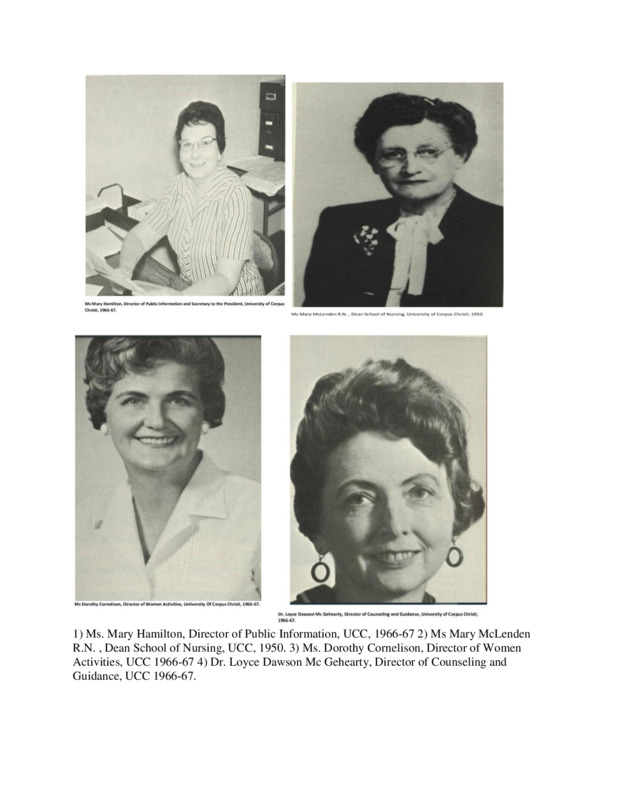

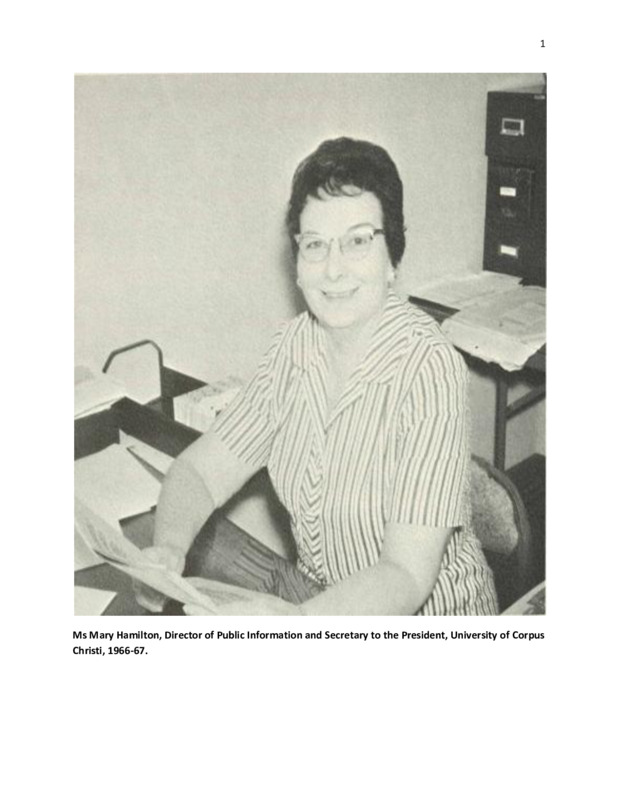

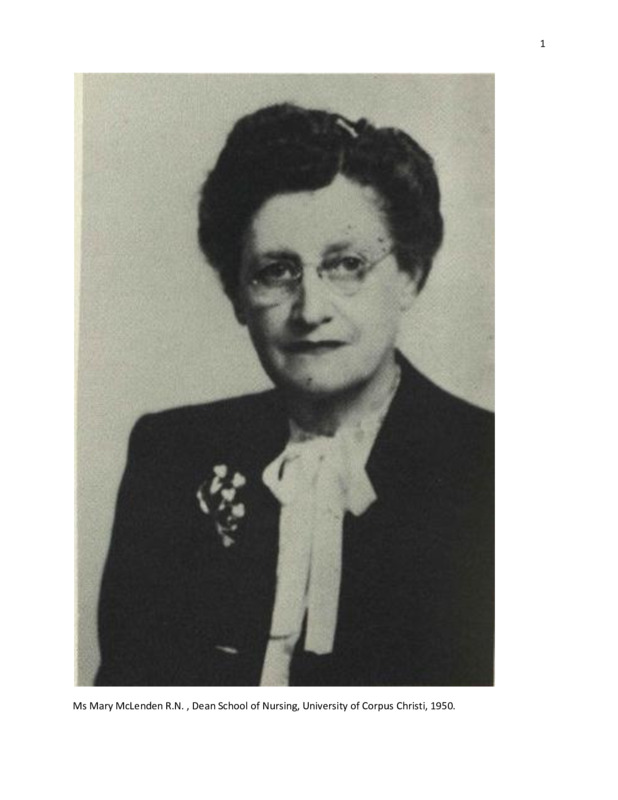

Women in Leadership Roles in Higher Education: From the analysis of the archive resource material like the student yearbook, titled The Silver King, published in the years 1948, 1950 and (renamed UCC) in 1966-67, it is evident that several women were appointed in leadership roles since the early years of its establishment in 1947. However, it is interesting to note that currently the University has the first woman President in its history of 11 presidents and she is also currently holding the position of Chief Executive Officer (CEO). Some of the pictures of women in leadership roles along with positions they held from the past to the present (1947-2023) are presented below for reference.

1) Ms. Arch Hunt, Assistant Registrar, UCC, 1948 2) Ms. Leonora Dorsey, Dean of Women, UCC, 1950, 3) Ms Adele Henderson, Director, Evening College, UCC, 1950 4) Ms. Mary Etta Hall, Dorm Director, UCC, 1950.

1) Ms. Mary Hamilton, Director of Public Information, UCC, 1966-67 2) Ms. Mary McLenden R.N., Dean School of Nursing, UCC, 1950. 3) Ms. Dorothy Cornelison, Director of Women Activities, UCC 1966-67 4) Dr. Loyce Dawson Mc Gehearty, Director of Counseling and Guidance, UCC 1966-67.

Women in leadership roles in the current Office of the Provost

Dr. Clarenda Phillips Dr. Susan Wolff Murphy

Provost & Vice President Associate Provost

for Academic Affairs

Margaret Dechant Melissa “Missy” Chapa

Associate Vice President for University Registrar

Student & Community Relations

Ms Kelly Marie Miller, First Woman President of Texas A&M University (1917 till date):

University Presidents, Past to Present, (1947- 2023)

|

Presidents of TAMUCC |

years as president |

Kelly M. Miller |

|

||

|

1 |

E. S. Hutcherson |

(1947–1948) |

|

|

|

|

2 |

R. M. Cavness |

(1948–1951) |

11th President of Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi |

|

|

|

3 |

W. A. Miller |

(1952–1965) |

|

||

|

4 |

Joseph Clapp |

(1966–1968) |

Assumed office |

|

|

|

5 |

Leonard Holloway |

(1968–1969) |

Preceded by Flavius C. Killebrew |

|

|

|

6 |

Kenneth Maroney |

(1969–1973) |

Personal details |

|

|

|

7 |

Whitney D. Halladay |

(1973–1977) |

Citizenship United States |

|

|

|

8 |

Barney Alan Sugg |

(1977–1989) |

Children 1 |

|

|

|

9 |

Robert R. Furgason |

(1990–2004) |

Education University of Pittsburgh, 1989 M.S. 1992, Ph.D. in speech communication, 1994, Pennsylvania State University |

|

|

|

10 |

(2004–2016) |

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

(2017–present) |

|

|

|

|

Ms Kelly Marie Miller, First Woman President of Texas A&M University (1917 till date):

Brief introduction: After receiving her Ph.D. in speech communication from Pennsylvania State University in 1994, Ms. Miller became the youngest full-time faculty member in the Department of Communication at Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi (TAMUCC). She taught leadership and business in her other courses as well. Ms. Miller previously served as the College of Liberal Arts Dean, Chair of The Department of Communication And Theater, Director of The School Of Arts, Media, And Communication, and Provost and Vice President for academic affairs before being named Texas A&M University's first female president [10]. Ms. Miller was the only candidate for president in June of that year, and she was appointed interim president of TAMUCC in January of that year. After a short meeting on June 19, 2017, the board of regents of the Texas A&M University System declared her president.

Implications: The presence of women in leadership roles in higher education has various implications that transcend beyond the individual institutions and impact society as a whole. Some key implications are:

According to Brent D. Rubin (2004)., author of the book Pursuing Excellence in Higher Education: Eight Fundamental Challenges, “Extraordinary challenges face higher education nationally, and leaders with exceptional capabilities are needed to help institutions meet these challenges” [11]. The complex challenges and ever-evolving or changing higher education landscape with diversity as its hall mark necessitate new forms of skilled leadership which the existing post secondary institutions lack .The fact that there are still not enough women in positions of such critical responsibility as president, provost, vice president, dean, director, and chair of a department is one factor contributing to the ongoing shortage of qualified leaders (Airini et al., 2011; The White House Project, 2009) [12].

Both students and faculty bring their lived experience, background, and perspectives to universities/campuses with them. A diverse faculty means a broader curriculum for students to experience, as well as exposure to a diversity of pedagogies, subject matter, and worldviews. Diversity in the student body gives young people fresh perspectives on various lifestyle and thought processes. The cultivation of broader minds, empathy, and tolerance for differing opinions is crucial for students when they step into a diverse and global society after graduation. Universities thus need to ensure that they hire a diverse staff that students can look up to as their role models and inspire them to dream big and achieve them.

Women in leadership roles can contribute to greater diversity and inclusivity in higher education as they bring a variety of perspectives, experiences, and problem-solving skills with them and diversity is a catalyst for the direction and intensity of campus community. Thus when more women are empowered to lead, everyone benefits in the society. Decades of studies show women leaders help increase productivity, enhance collaboration, inspire organizational dedication, and improve fairness. For instance, the nature of the research and the type of questions posed and the conclusions drawn from research are impacted when female academics participate. Similarly, when successful women leaders work, they are likely to influence female and male students, faculty, and staff perceptions of women in leadership roles. These women can also serve as mentors and role models to younger women who are on their path to leadership.

A meta-analysis of over 160 studies on sex-related differences found that women use a less autocratic or directive (agentic) style and a more democratic or participatory (communal) style than men (Eagly & Johnson, 1990) [13]. Additional research conducted on team performance, leadership, and influence indicated that men tend to be more assertive and dominant and show less warmth and deference to their teammates than do women (Carli & Eagly, (1999) [14]. "Female managers are more likely than male managers to embrace a transformational leadership style, particularly when it comes to mentoring and providing individual attention to their subordinates," claim Eagly, Johannesen-Schmidt, and Van Engen (2003) [15].

Several studies using 360-degree feedback methods show that behavioral competencies like information sharing, teamwork, empowerment, and employee care are more highly scored by female managers and executives. According to other research on leadership skills, men tend to be more optimistic, self-assured, flexible, and capable of handling stress, while women tend to be more sensitive to their feelings, empathetic, and skilled in interpersonal interactions leadership style, especially in terms of coaching and giving each subordinate their full attention. (Goleman, 1998) [16].

Conclusion: In the context of U.S. politics and communities becoming increasingly divisive in the past decade and to achieve Biden administration's goal of creating a federal workforce that reflects the diversity of the United State, there is need to increasing the number of women in leadership positions across all industries, including higher education. Gender gaps still persist in higher education, and women are frequently underrepresented in positions of high leadership, such as chancellor and president of universities. Hence, if not for gender parity, at least for advancement of diversity, equity, and inclusion, men in positions of leadership need to actively support women's advancement in leadership roles in higher education because higher education can and must play a role in creating educated, open-minded, and strong communities by allowing everyone the access to educational opportunities. Dr. Gee correctly noted, "Leadership is not a solitary endeavor; a major portion of it involves supporting others and supporting others is a natural trait of woman [17].

References

[12] Airini, Collings, S. Lindsey, C., McPhers, K., Midson, B., and Wilson, C. (2011). Learning to be leaders in higher education: what helps or hinders women’s advancement as leaders in universities, Volume 39, Issue 1. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143210383896,

[11] Brent D. Ruben (2003): Pursuing excellence in higher education: eight fundamental challenges, ISBN: 978-0-787-96204-3

[6] Caitlin, C. (2021). Texas A&M University division of marketing & communications. reflections on being a woman in higher education.four Texas A&M leaders experiences as part of a student government association "maroon table talk."

[13] Eagly, H. A., Johnson, T. B.(1990). Gender and leadership style: A meta-analysis. : https://opencommons.uconn.edu/chip_docs

[14] Carli, L. L., & Eagly, A. H. (1999). Gender effects on social influence and emergent in G. N. Powell (Ed.), Handbook of gender and work (pp. 203–222). Sage Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452231365... Courtesy of Bradley University, Diversity in Higher Education: Statistics, Gaps, and Resources

[15] Eagly, A. H., Johannesen-Schmidt, M. C., & Van Engen, M. L. (2003). Transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership styles: A meta-analysis comparing women and men. Psychological Bulletin, 129(4), 569–591. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.569

[2] Ely J. R., & Kolb, M.D., (2013). Women rising: The unseen barriers, The Harvard business review (gender).

[5] Fuesting, Bichsel & Schmidt, (2020): Faculty in higher education, annual report for the year 2019-20.

[6], [7], [17]. Gee, G. C. The UTSA Academic Affairs, Career-engaged learning of the university of Texas at San Antonio.

[16] Goleman, D. (2008). The emotional intelligence of leaders https://doi.org/10.1002/ltl.40619981008

[12] Jones, K., Karen, A. A., Longman, R (2018): Perspectives on women’s higher education leadership from around the world special issue, published online in the open access journal administrative sciences (ISSN 2076-3387).

[1] Kalnicky, E. and Shutava, N. (2022). Leadership and gender differences in the federal government and beyond: How women lead series

[9] Kelly M. Quintanilla, Ph.D.Interim President, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi". Visit Corpus Christi Tx. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

[8] U.S. News & World Report 90th Ed, Best College Rankings, https://www.usnews.com, Education, Colleges

[3], [4] Williams, C. D. (2021). Investing in and supporting women’s leadership in higher education. Higher ed jobs.